I was fortunate to be able to spend three weeks at the family lake house in northwestern Michigan in August. My father passed away in 2009, but his imprint is still palpable there on the lake—nowhere more strongly than on the bookshelves.

My son John and his wife Julie were able to join us for one of our weeks. John’s an amazing, intuitive, creative cook. He’s also strongly attracted to Old Things, so, for example, he snagged and regularly wears most of my father’s outerwear including an enormous ’70s-era Eddie Bauer winter parka and a tired out, ugly-as-sin L.L. Bean fleece.

At the intersection of cooking and Old Things, John has an unsurprising fascination with legacy recipes, such as (grandfather) Papa Tom’s Peach Cobbler, which he’s tweaked to a state of perfection. He likewise loves heirloom kitchen gear, and again has snagged a number of family classics, some dating back to almost to WW2, including Papa Tom’s biscuit cutter and (great grandmother) Ma’s classic heavy roasting pot.

A Book Encounter

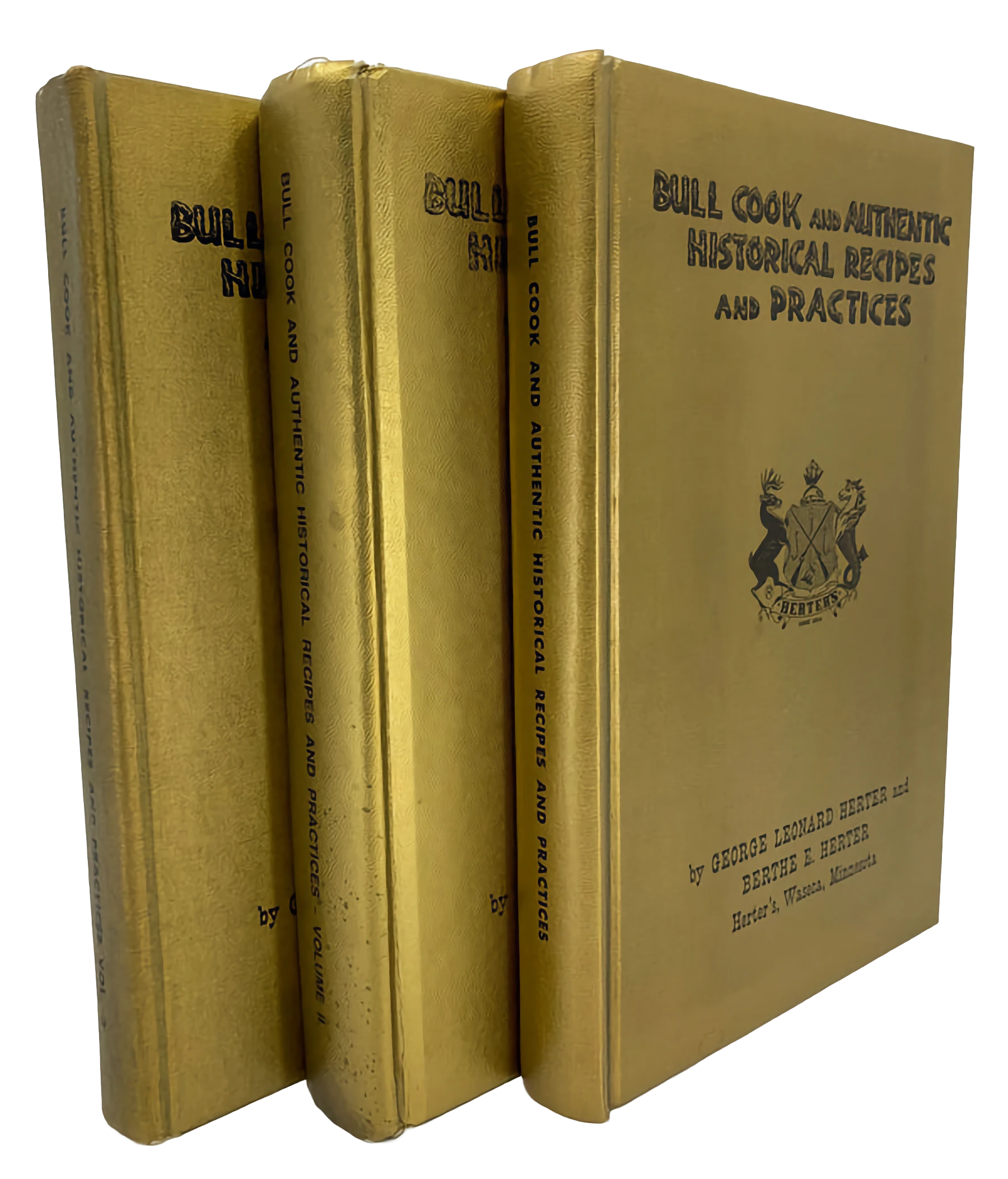

While browsing the lake house bookshelves, John stumbled across Bull Cook and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices and was immediately hooked. And if you’re a creative cook who’s into Old Things, what’s not to love—it’s an insane collection of historical recipes and random factoids, itself written back in prehistoric 1960, with many recipes dating centuries further back. I can recall my father’s enthusiasm for the book, along with its author George Leonard Herter and his catalog business Herter’s.

As John paged through the physical Bull Cook, I opened my iPad to follow along online, confident I’d quickly locate some free PDF version online, because Bull Cook was 73 years past its first edition date, and moreover wasn’t a “real” book anyway, but rather was self-published by Herter. As you might suspect from its unique cover:

Surprise! I did not quickly locate Bull Cook online. Eventually, thanks to the Internet Archive’s Open Library, I was able to read the book online, in an awkward web UI, by checking out the one available virtual copy, one hour at a time.

I began pulling on the thread of Bull Cook and its strange unavailability; much unravelling ensued.

Herter’s, The Business

In 1937, George Herter launched his disruptive startup—a mail-order outdoor-sports business—in the spare rooms over his father’s Waseca, Minnesota dry goods store. Disruptive? Well, yes. Sears had pioneered the mail-order catalog business almost 40 years earlier, but Herter had the insight that the same concept might work in a much smaller niche market that was, at the time, served by mom-and-pop storefronts. In 1937, mail order was as innovative and disruptive as e-commerce in 1999. So, yes, a disruptive startup it was.

Over the following 40+ years, Herter’s came to dominate its fishing-hunting-outdoor niche, first with mail order, and later, outlet stores; the same space and strategy that today is the domain of Cabela’s and its parent Bass Pro Shops.

Herter’s and Cabela’s overlapped by 20-odd years, with Cabela’s starting up in 1961, and Herter’s filing for bankruptcy in 1981. Herter’s assets ended up with Cabela’s through the liquidation process.

Self-Publishing

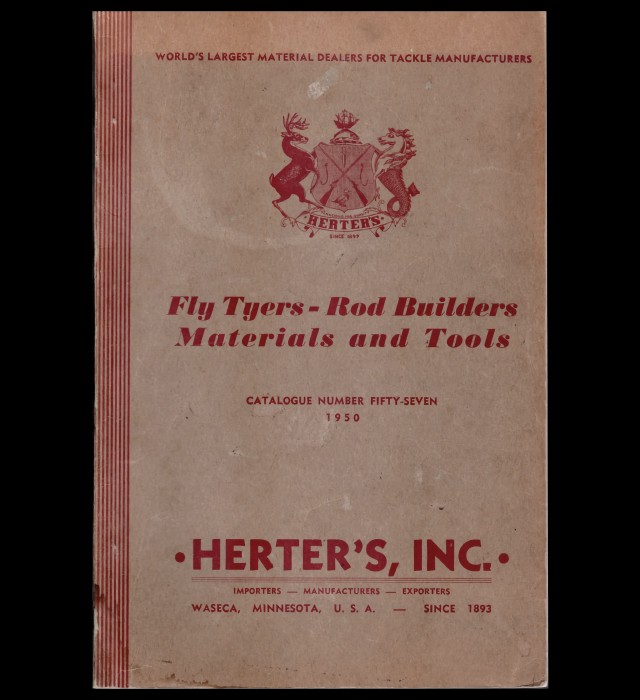

Pre-internet, every successful mail order business was also a publishing business, because—catalogs. At its peak, for example, Sears printed 315 million copies of its main catalog every year, along with millions of additional copies of specialty catalogs such as its Christmas “Wish Book.” That’s the book sales equivalent of 20 blockbusters, or 1,500 average bestsellers, according to my research assistant GPT-4.

Herter’s was smaller, but still a significant publisher, with regular printing runs of 400K to 500K copies for the often 600+ page Herter’s Catalog—equivalent to a couple of juicy bestsellers annually. In fact, according to Paul Collins’ 2008 New York Times article The Oddball Know-It-All, Herter’s catalog printer Brown Printing, also located in Waseca, MN, grew with Herter’s to become “one of the country’s largest commercial printers.”

All this to say: self-publishing Bull Cook wasn’t any kind of an obstacle for George Herter.

What’s a Bull Cook?

To be honest, I was confused by the book’s title, partly because I was unfamiliar with the term “Bull Cook”—I thought it might be a person—and partly because, even with an understanding of what a bull cook is, the title still doesn’t exactly make sense. Paul Collins describes Herter’s writing has as having “the artless charm of a confused book report” and that confused thinking seems to have found its way into Bull Cook’s title as well.

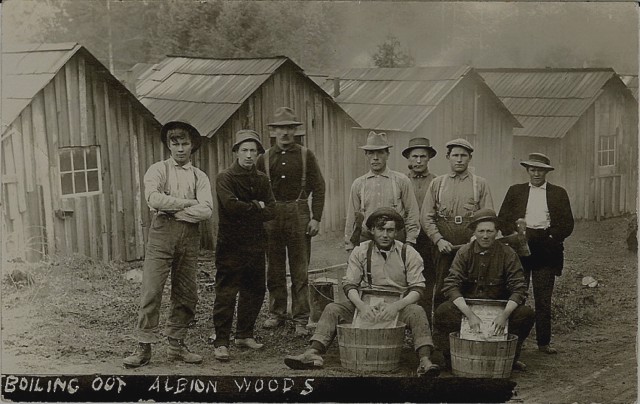

I eventually got around to asking my preferred search companion Kagi “What’s a bull cook?” and got an immediate answer. Bull cook is a logging term—makes sense given Herter’s Minnesota roots—and it means, according to Merriam Webster:

bull cook (noun)

: a handyman in a camp (as of loggers)

especially : one who does caretaking chores and acts as cook’s helper

Etymology

so called from his job of caring for oxen once used in logging camps

One of the gentlemen below is supposedly a bull cook. My money’s on washtub left or washtub right.

Wacky Author, Wacky Subject Matter, Good Recipes

I’ll follow Paul Collins’ lead and quote from the third paragraph to give you a feel for Bull Cook’s subject matter:

For your convenience, I will start with meats, fish, eggs, soup and sauces, sandwiches, vegetables, the art of French frying, desserts, how to dress game, how to properly sharpen a knife, how to make wines and beer, what to do in case of hydrogen or cobalt bomb attack. Keeping as much in alphabetical order as possible.

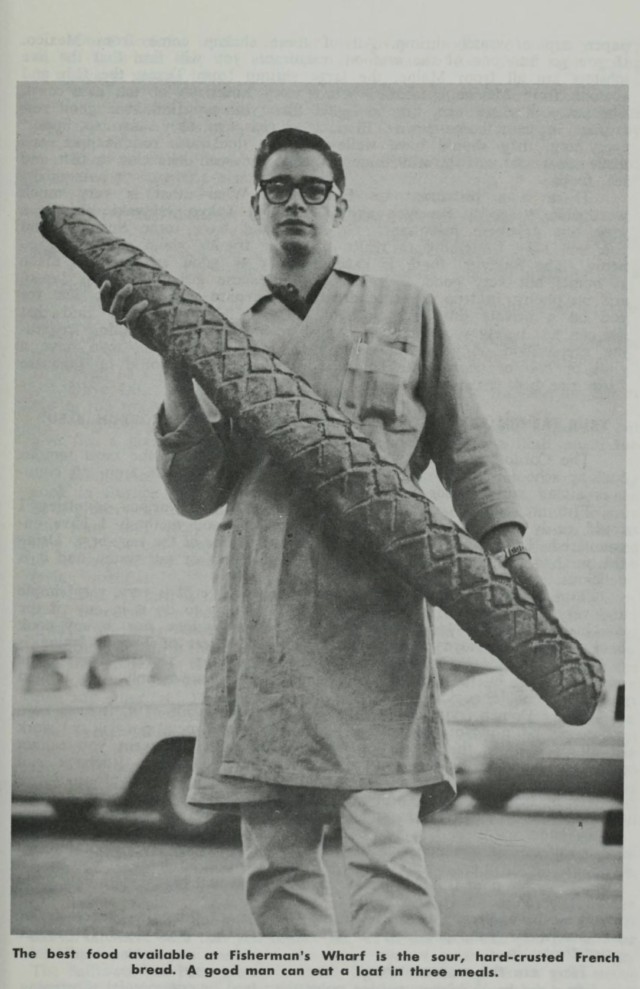

Nothing like mixing in a little nuclear attack drama to spice up the intro page. You can jump to page 206 for that advice around hydrogen or cobalt bomb attacks—presented in the context of preserving tomatoes. Herter’s range is demonstrated in a random selection of pages: 42 (How to Prepare Javelina) and 223 (Fisherman’s Wharf French bread).

The book’s very first recipe explains how to properly “corn” meats as in corned beef, and here Herter displays his gift of bombast:

Although some cook books and food editors of magazines from time to time publish recipes for corning meat these recipes are not even close to the real one. This is the first time the real authentic recipe for corning meat has ever been published.

One commenter quipped of the voluminous Herter’s catalogs that “if all the BS was out of them they’d only be a half dozen pages long,” and the same perhaps might be said of Bull Cook. But the recipes are apparently real and good according to those that have made them; I saw nothing ingredient- or procedure-wise that would make me feel otherwise.

Copyright Status: Murky

So Herter’s died as a business in 1981; George Leonard Herter as a human in 1994; so why are Bull Cook and the rest of George Leonard’s writings not living on in the public domain? Who in the world would care?

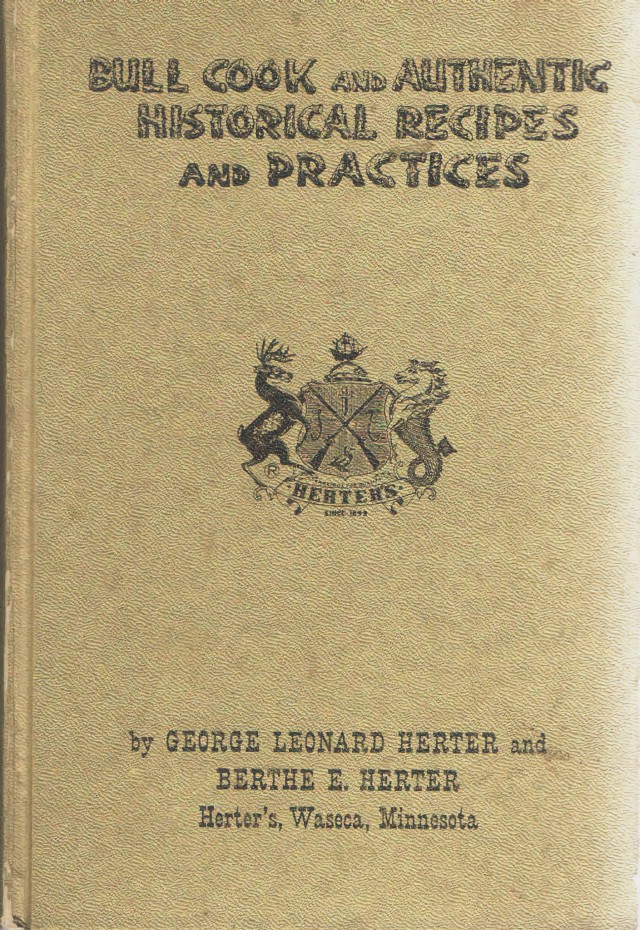

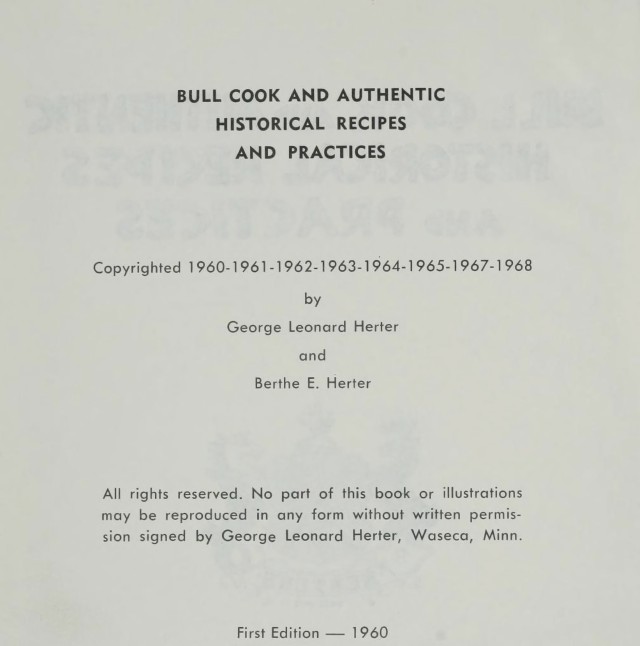

Below is the copyright page of the 12th edition; it’s clearly in George and wife Berthe’s name, as opposed to copyrighted by the business.

But the book’s actual copyright status today remains murky. Copyright, with a deceased author, an initial publication date before 1978, and a possibly related bankruptcy, makes a messy mix. These days, copyright is automatically extended 70 years past the author’s death. But pre-1978, an initial copyright provided 28 years of protection, and the author was required to register the copyright to get extended protection. In my light and not necessarily expert research, I didn’t turn up any such registration for the initial volume of Bull Cook (apparently there were as many as four volumes). I don’t know whether Herter himself went bankrupt, or just his business; whether he assigned rights to his books, potentially in his will; what do family members know about all of this; and so on.

One could summarize the gist of U.S. copyright laws as guilty (of copyright infringement) until proven innocent. With so many unknowns here, Bull Cook seems to be stuck in copyright purgatory, and our best option to consume it is one hour at a time on the Internet Archive.

But Wait, It’s on (sc)Amazon!

And here we arrive at another surprise turn of events. During my initial searches, I had gotten hits for Bull Cook on Amazon. When I clicked through, though, it didn’t look like the same book—the cover was completely different and totally sketchy, check it out:

At the time, I wasn’t interested in a sketchy and expensive print edition so I moved on. But in researching the copyright question, I circled back to Bull Cook’s Amazon listings, just to see what I might learn about the book’s copyright status. I found that Bull Cook on Amazon was published in 2012 (!!) by a company called Literary Licensing, LLC, of Whitefish, Montana; and is sold by Amazon themselves. Literary appears to be in the reprinting / print-on-demand business. That category itself is a scam magnet (e.g. ultra-expensive, poor-quality photocopied textbooks), but Literary might be in a scam-class of their own. Here’s their website, where they proudly proclaim themselves to be a “Publisher of Fine Books”:

Note that I didn’t say “home page” of Literary Licensing, because—that one screen is the whole damn website. It does have a search bar, but it just forwards you to an Amazon search for the term you enter, filtered for Literary’s titles. Furthermore, I’m not sure what the tropical beach scene has to do with Whitefish or fine books. Oh, wait, that’s an Unsplash image. OH WAIT this is a Squarespace site. I’m guessing Literary invested at least 15 minutes creating their home on the Internet, maybe even 20. Not confidence-inspiring.

Publisher of Fine Books

It appears, based on what I’m seeing and reading—and I don’t know for sure, just sharing my intuition here—that Literary Licensing lives somewhere in the spectrum from unethical-but-mostly-legal through totally-a-scam. For example, check out this series of posts relating to Literary Licensing / Kessinger Publishing. I haven’t dug deep, but something smells here. Like a putrefying raccoon carcass.

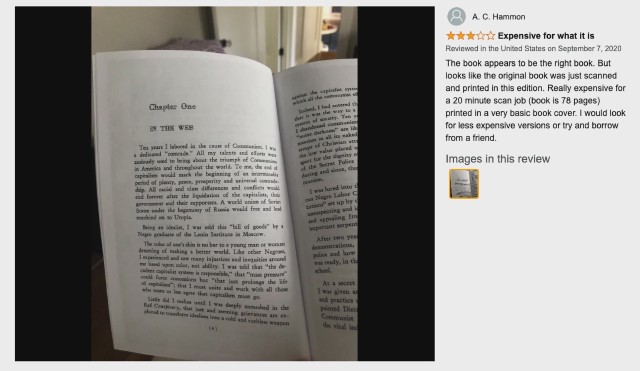

So what might be going on in our case with the Bull Cook reprint? My guess is, somehow Bull Cook showed up on Literary’s radar as “there might be some demand for a reprint of this out-of-print book,” perhaps from a signal such as used copies selling at a premium. Literary might then create a premium-priced listing on Amazon, and start taking orders. When orders roll in, Literary could then scan or find a scan of the book, slap their lovely cover on it, and fulfill via print-on-demand. Here’s a review of another Literary-published book on Amazon—the buyer is none too pleased at how much they paid for a poor photocopy:

Where’s the “check copyright, secure a license for the materials” etc. step here? Based on what’s I’ve seen reported about other books published by Literary, I suspect Literary might just skip that step, and instead just go ahead and list, sell, print, figuring that nobody will notice or care. If you’re a big fish in a small place like Whitefish, MT, you might be really tough to successfully sue.

There appears to be a related scam where a fairly current, somewhat popular book lacks one of Amazon’s formats, such as “hardcover,” and Literary appears to step in and list a poor-quality, overpriced reprint to fill that gap. In this case, you would think that the rightsholder gets compensated somehow … but you never know. I don’t understand Amazon’s rules around this, but clearly scammers seem to have found a way to thrive here.

Now get this—Literary Licensing, LLC appears to have 50,000 listings on Amazon. The scale is pretty staggering here, reminding me of the massive fake mobile app scams on the Play Store and App Store. There’s also a strong smell of alt-right-wacko in the selection of titles, possibly another Literary characteristic.

Amazon usually keeps scammers at arms-length, just fulfilling orders (“Ships from”) but not taking on the liability of being the seller of record (“Sold by”). So in this case, if Literary is in fact a scammer, it seems like Amazon is taking on liability for that scam.

What Stinks Here

- That Bull Cook and other George Leonard Herter books aren’t simply out there, public domain, easily accessible.

- The U.S.’s overly-protective copyright laws—the same ones that the Google Books project is still mired in.

- Fake re-publisher/scammers taking advantage of public domain or inadequately protected copyrighted material

- Amazon looking the other way, as they are known to do elsewhere when it suits their purposes

What Doesn’t Stink Here

- Bull Cook’s fun recipes, authentic outdoor guide wisdom, crazy stories, and hilarious questionable facts

- Organizations like the Internet Archive that work to preserve and disseminate interesting content like Bull Cook

I’ve pulled enough threads on this one, time to finish up. I enjoyed the journey and intend to try out some Bull Cook recipes soon.